Introducing the Thali Model

A simple tool to transform maternal nutrition.

Pregnancy is a profound and transformative experience in a person’s life. But amidst the joy, navigating all of the advice on how to take good care of themselves and their unborn child — including dietary guidance — can be as challenging as finding one’s way through a maze, especially for mothers and families with low-literacy or those from socio-economically marginalized communities.

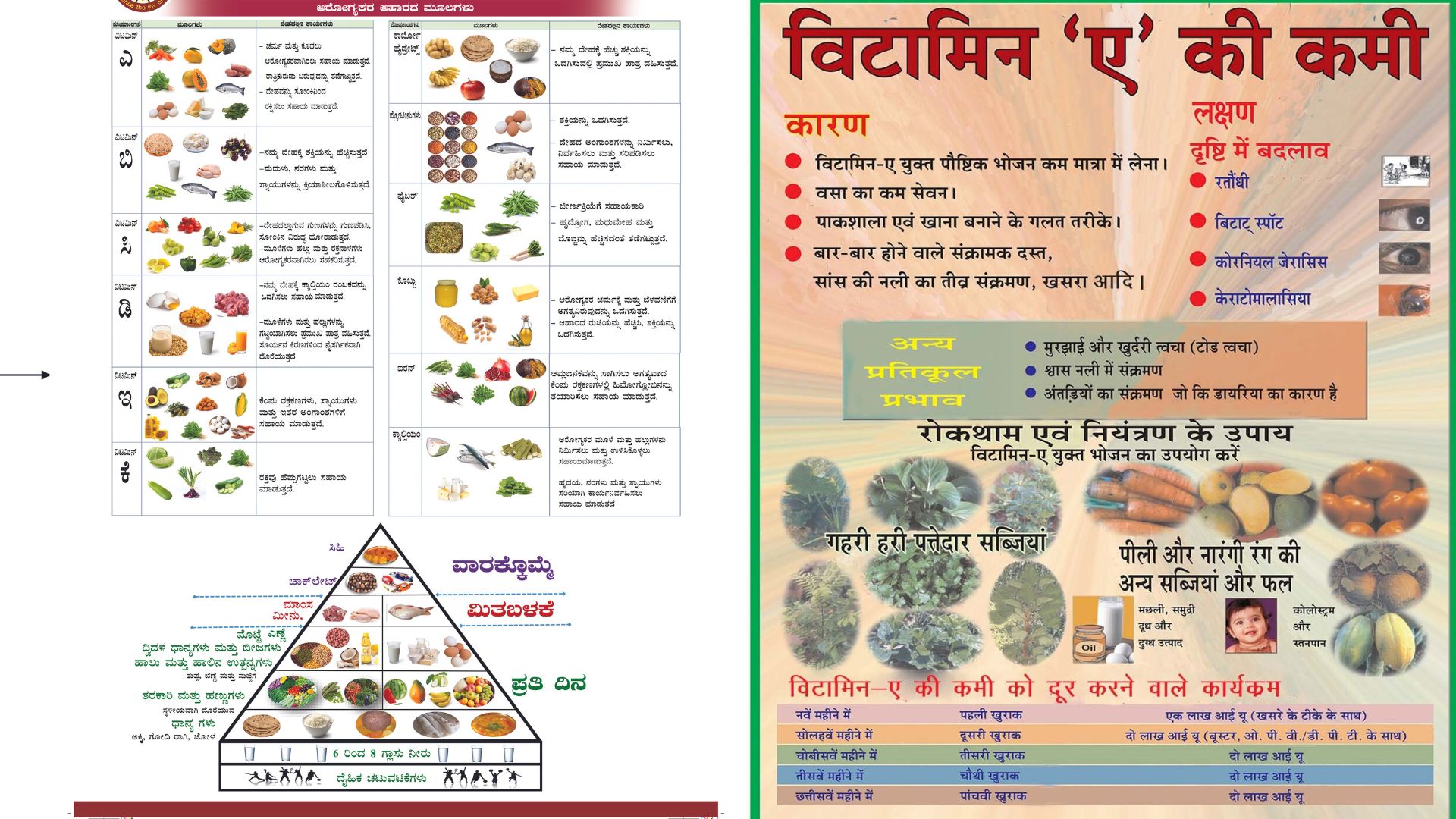

Unfortunately, the nutrition guidance provided in most Indian hospitals often takes the form of complex, text-heavy food pyramids or confusing nutrition percentage charts. For expectant mothers and their families, these resources — though well-intentioned — can be as bewildering as an ancient treasure map, complete with cryptic symbols and riddles, pointing to food items that might be exotic, unaffordable, or simply beyond reach.

Resolving this culinary conundrum

Providing nutrition guidance is a crucial component of Noora Health’s antenatal and postnatal Care Companion Program. To ensure that our trainings provide contextual, relevant, and accessible information, we set out to design a simple tool to help pregnant mothers and caregivers visualize a healthy meal.

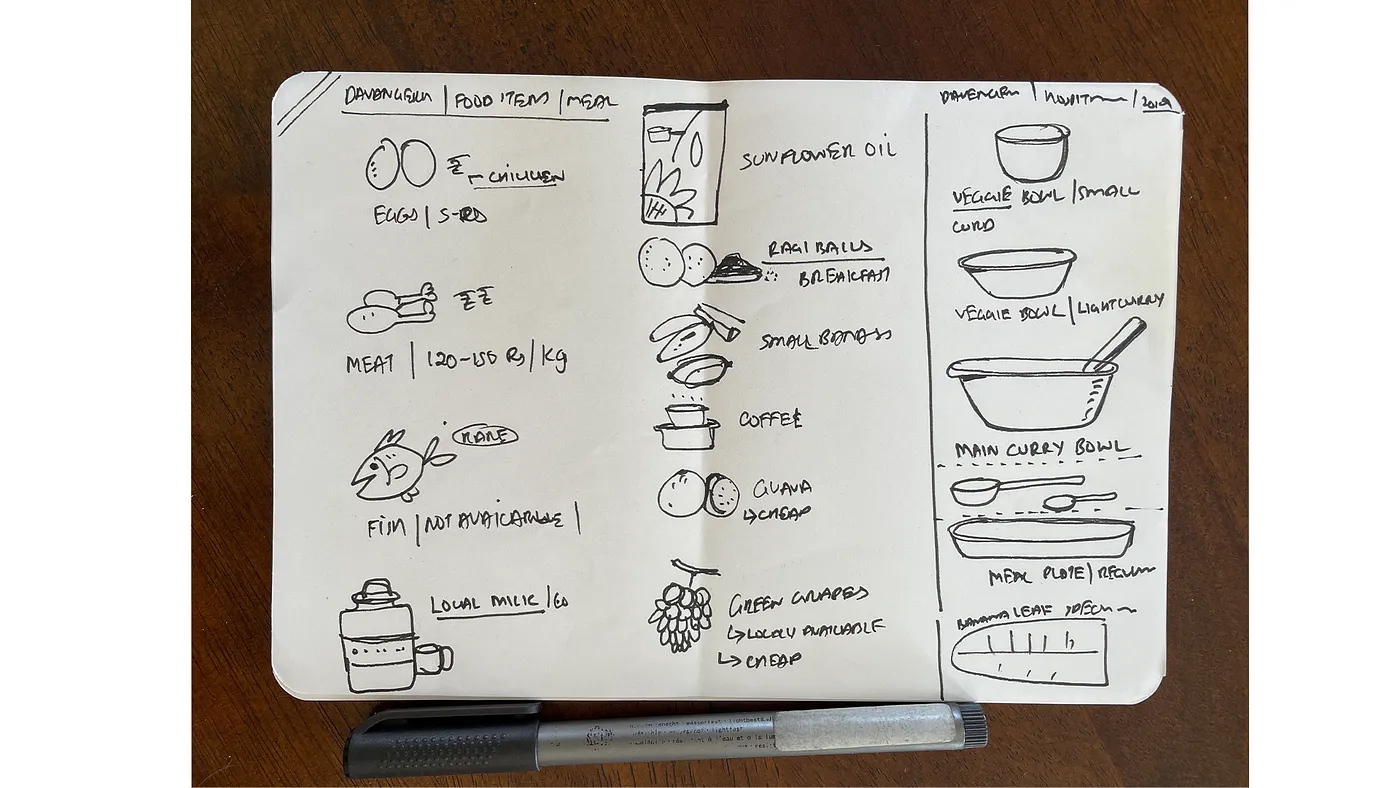

First, we spoke to mothers, caregivers, nurses, and local shopkeepers across Davanagere district, Karnataka, to understand more about locally available food items and their usual food purchase patterns. Snippets of what they shared include:

- “We just buy whatever’s available at the nearest shop.”

- “We prefer seasonal, affordable fruits, vegetables, and grains in our meals.”

- “You know, we only eat expensive items like meat during special occasions.”

- “When we eat, it’s pretty straightforward — the meals are on plates, and those katoris (bowls) are for our curries and vegetables.”

With this information in hand, and under the expert guidance of the Noora Health medical team, we embarked on the design process.

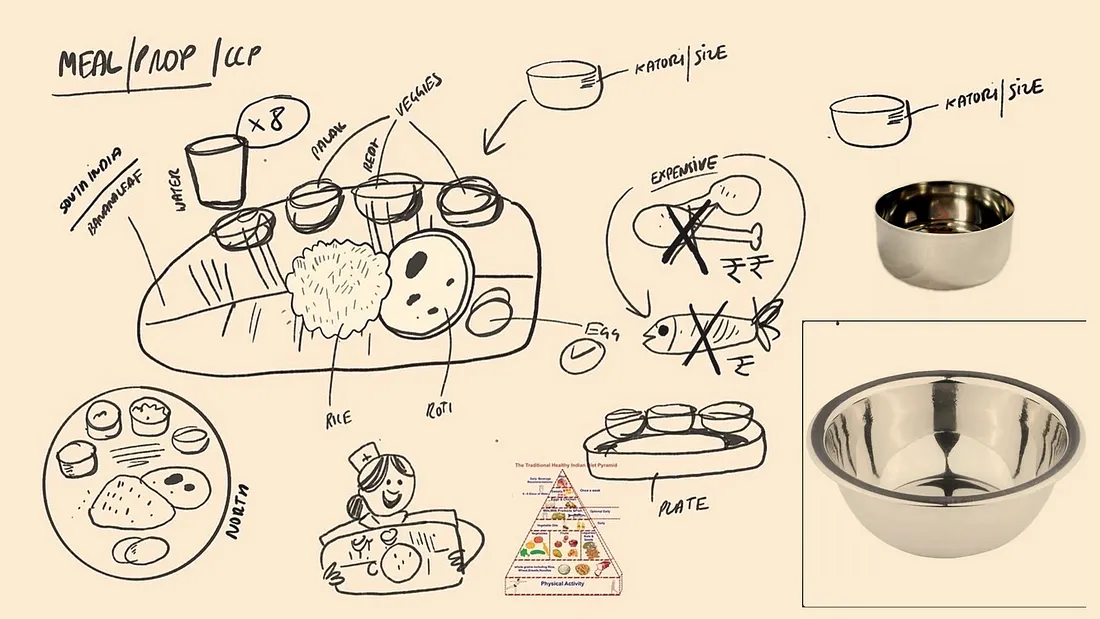

Designing for clarity

Imagine a plate; not just any plate, but a thali — a plate laden with multiple dishes that is an emblem of India’s culinary diversity. Drawing inspiration from this, we decided to place the food items on a banana leaf, a common way of eating food across cultures in South India. Incorporating the government’s nutrition guidelines for mothers and children, we made sure to include different food groups in the design. To convey easy to understand portion sizes, we used various-sized katoris — those delightful bowls holding gravies, curd, or vegetables, that are ubiquitous in any Indian meal.

Once the tool was prototyped and tested (and tested again) in the Davanagere District Hospital, we printed it on a lightweight sunboard, making it both practical to carry and easy to use.

Observations and feedback

We disseminated sample copies of the tool across the hospitals we work at in Karnataka, inviting trainers to use them alongside other CCP collateral. We tried not to be too prescriptive in how the nurses used the tool, allowing them to interpret and adapt it to their context. The feedback we received was overwhelmingly positive:

- “This is nothing like what the government gives us.”

- “Holding this, I really feel like I’ve got a proper thali in my hands.”

- “Both mothers and families can’t wait to grab one of these. Everyone wants to take it home after the session.”

- “Every time we reveal the model, there’s so much curiosity and excitement in the air.”

In particular, we heard that having the banana leaf as a visual element in the final design helped the tool stand out from other infographics in a hospital. The visual presentation also simplified the information needed by mothers and families to follow a good diet.

The road ahead

In the four years since we originally piloted the tool, we have diversified, creating customized thalis for the different regions of India. For example, the proportion of rice shown in the South Indian thali is higher than that of North India, where more rotis are consumed.

We are constantly exploring new ways to simplify our model and provide more customization options. For instance, the initial design was not very convenient for nurses to carry around or store due to its large size. Therefore, we are currently working on making the tool more foldable and compact. Additionally, we have developed the thala model in Bangladesh which offers more locally-available food options for patients and caregivers to choose from. As Noora Health expands to Indonesia, we plan to provide an even richer tapestry of options for our users.

The success of our thali model is a testament to the importance of human-centered design and simple, relatable information in driving behavior change. It is a concept that transcends borders and cultures, and can be adapted to nourish expecting mothers in any corner of the world.