How did COVID-19 impact maternal and child health in India?

New mothers reported limited access to health services and family support — and higher anxiety levels.

Noora Health and Stanford Center for Health Education’s Digital Medic initiative began our partnership in 2018 to design and understand health behavior change within health education programs in Indian health systems. This article highlights what we’ve learned as part of our research collaboration (publication upcoming).

In mid-May 2020, when Jyothi was nine months pregnant with her first child, India was experiencing one of the strictest set of lockdown measures worldwide, in response to the rapidly spreading COVID-19 pandemic. Because of mobility restrictions in the state of Karnataka, Jyothi was unable to attend any doctor’s appointments. And when it was time to give birth, she was turned away from the government hospital where she had originally planned to deliver.

The hospital said that they were not conducting deliveries due to COVID-19. To make matters worse, she learned that her local community health worker was under quarantine. Luckily, in early June, she was able to give birth at a private hospital to a healthy baby boy with no complications. However, with the lockdown still in place, Jyothi — a first-time mother — was left without access to the healthcare and familial support structures she had hoped to rely on.

Unfortunately, as the pandemic spreads to nearly every corner of the globe, stories like Jyothi’s have become all too common. Evidence is mounting that individuals in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are being disproportionately affected by the pandemic. For mothers and children, the implications are particularly dire, not just due to the virus itself, but because of interrupted access to health services and economic impacts leading to food insecurity. Indeed, previous epidemics have resulted in decreased access to healthcare and increases in maternal and neonatal mortality. In May 2020, the United Nations identified new mothers as especially vulnerable due to increased household and caregiving tasks and disruptions to services and social support structures that are so critical in the early days of infant care.

Together, the Stanford Center for Health Education’s Digital Medic initiative and Noora Health collaborated to investigate the impact of the pandemic on new mothers during India’s lockdown from May 5 — June 22, 2020. Between May 10 and June 22, we reached out to a random sample of new mothers who had given birth at government district hospitals in the preceding six months and who had been previously enrolled in Noora Health’s Care Companion Program for antenatal and postnatal care in the states of Karnataka, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra.

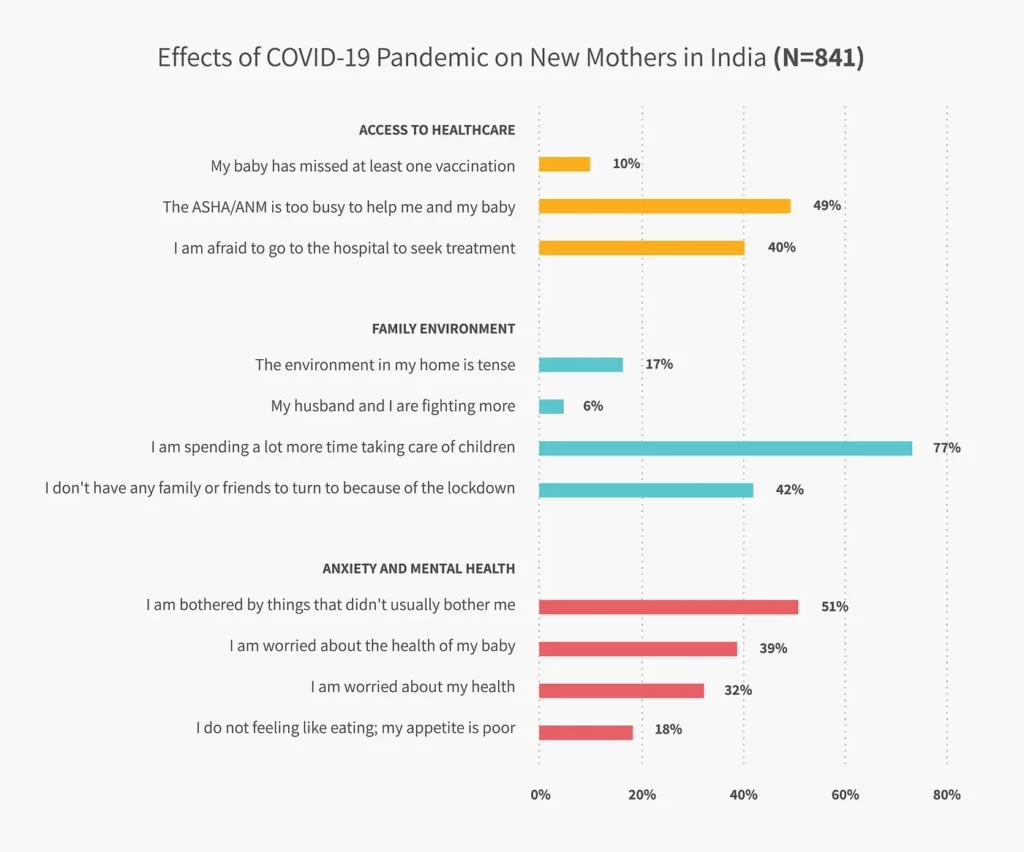

During a 25-minute phone survey, we asked mothers about their background and experiences during the lockdown. A total of 841 new mothers participated in the survey; 68 percent resided in villages and 65 percent lived below India’s poverty line. The average age of the babies (at the time of surveying) was nearly five months. What we found from these new mothers confirmed the many anecdotes being shared during this time — that their access to health services and family support had diminished and anxiety had increased.

1. Reduced access to healthcare

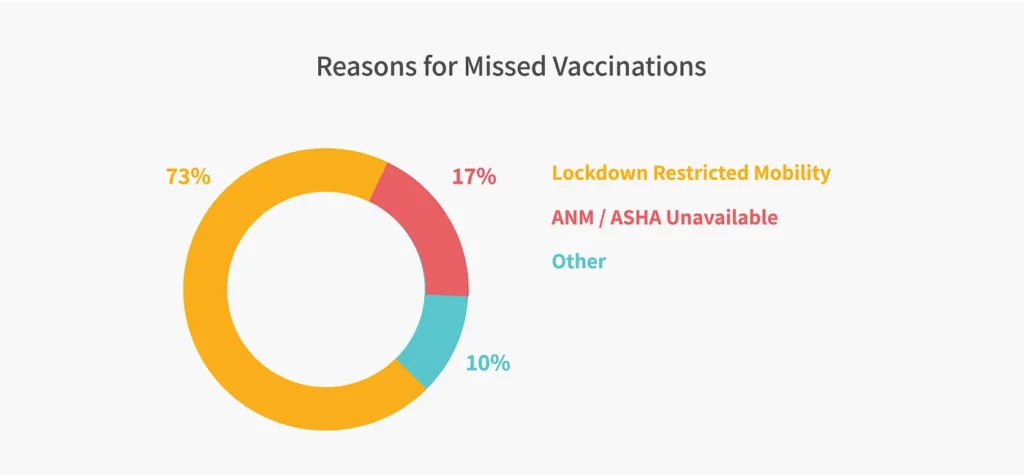

Of the mothers surveyed, 10 percent indicated that during the lockdown their baby had missed at least one recommended vaccination. Of these mothers whose babies had missed vaccinations, 73 percent attributed it to restrictions in mobility and another 10 percent to the unavailability of ASHAs and ANMs (frontline health worker staff who support antenatal and postnatal care for families) in their community. Nearly half of the mothers (49 percent) indicated that the ASHA or ANM was too busy to help them or their baby during the lockdown. This is reflective of the additional COVID-19 duties that ASHAs and ANMs had to take on during the pandemic. Forty percent of mothers also indicated that they were afraid to seek treatment from a hospital if needed.

2. Limited family support

Seventeen percent of new mothers reported a tense home environment and 77 percent indicated they were spending more time taking care of children during the lockdown. Forty-two percent also indicated that they don’t have any family or friends to turn to for help because of the lockdown.

3. Poor mental health

More than half (51 percent) of the mothers surveyed indicated they were worried about things that didn’t usually bother them. Roughly a third mentioned that they were worried about their own health or the health of their baby. Eighteen percent of mothers indicated they did not feel like eating and had a poor appetite.

4. Increased food insecurity

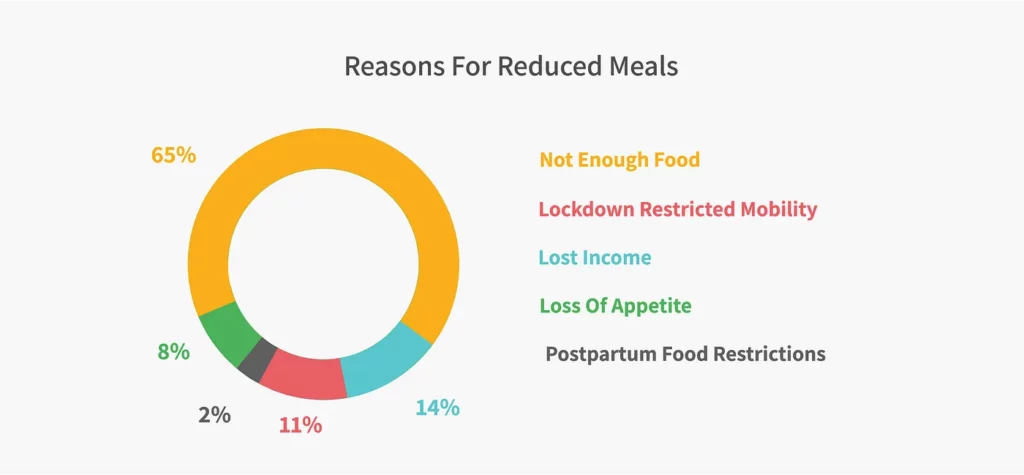

Across all mothers surveyed, 20 percent indicated that they had reduced the number of meals they ate during lockdown. Poor appetite explains only about 8 percent of this reduction. Instead, the reduction in meals among new mothers appears to be caused by food insecurity due to the pandemic. Twenty-three percent of all mothers surveyed reported finding it difficult to purchase food during the lockdown. Among the 20 percent of mothers who had reduced their meals, 65 percent said the main reason was not having enough food and another 14 percent attributed it to a loss in household income. Eleven percent named restricted mobility as the cause of reduced eating.

5. Knowledge gaps

Another stark finding of the survey revealed a lack of knowledge among mothers about how to protect themselves and their families from the risks of COVID-19. Despite the pervasive spread of the disease, only 17 percent of mothers felt that they personally were at risk of infection. Among those who felt that they were not at risk, 29 percent reported that they were taking no precautions at all to avoid getting sick.

Rethinking health education in the context of COVID-19

In light of these findings, the need for accurate and effective digital health messaging appears greater than ever. As part of the Care Companion Program, Noora Health provides a Whatsapp-based messaging service for two-way communication, which sends push messages on maternal and newborn care to mothers. The service also allows mothers and their family caregivers to ask questions and receive medically-informed advice. When the lockdown began, a flurry of questions from participants like Jyothi began rolling in, underscoring the importance of remote follow up during this time.

“I am six months pregnant, and I should get my tetanus vaccination. But because of the coronavirus, the government hospital is not giving injections. What do I do if I miss the second dose of my vaccination?”

“My baby is one month old and has a fever. Because of the lockdown, we are not able to take the baby to the hospital. What do I do?”

“Puss is coming from my baby’s [umbilical] cord area, but because of the lockdown I can’t go to a hospital. Please help with treatment.”

“Because of the lockdown, I can’t go for a [health] check up. How long should I take calcium and iron? Do I need to take any other medicine?”

Findings from this survey shed light on specific challenges COVID-19 and the lockdown had brought to new mothers at home while raising newborns. In the absence of in-person interactions, technology is bringing about a fundamental shift in the way that health information can be relayed and services delivered. Digital Medic and Noora Health are working hard to design effective digital tools that can help to fill these critical gaps in health knowledge, designed for audiences in India and globally.

New mothers need to be better supported and informed to protect themselves and their families to ensure that, as best as possible, they are doing what they can to follow recommended guidelines for care in the perinatal period. We aim to do just that and continue centering our research, design of products and services, and implementation activities around what new mothers and caregivers need most.

Jamie Johnston and Pooja Suri of Digital Medic and Sahana SD, Seema Murthy, and Shirley Yan of Noora Health, contributed to this article.

This article was originally published on Sep 28, 2020 and edited and updated in July 2023.